Followership is an area of study in leadership and refers to the role and behaviors of individuals within a group or organization who align themselves with a leader and contribute to the achievement of common goals. While leadership often takes the spotlight, followership is an equally essential and dynamic component of any organizational structure. Followership is not a passive role; it involves active engagement, collaboration, and a sense of shared purpose. Successful organizations thrive when there is a balance between effective leadership and followership, with both roles contributing to the overall success and well-being of the group and organization.

The reality is we have all experienced followership. We’ve followed friends during recess, teachers in class, supervisors at work, or board presidents in organizations. However, we’ve not always recognized when we were following or consciously thought about improving our followership skills. We tend to believe we are good followers when we follow a leader’s directions, complete a given project, or apply a board member’s advice.

Some may argue they’ve always been good followers, but they weren’t supervising themselves. From my experience, being a good follower shares similarities with being a good leader – good and frequent communication, self-awareness, good work ethic, trustworthiness, and active listening (among other things). But, we rarely ask ourselves if we are showcasing these traits, how we could be better followers, or how we could support our leaders more effectively.

Some of us have supervised others. Each follower brings unique personalities, experiences, needs, and desires. It wasn’t until I managed a full team that I began to understand the intricacies of good followership and leadership. I realized that you never truly feel confident in your leadership abilities because your leadership style must constantly adapt. This adaptation is necessary because people are always changing, making leadership inherently situational.

In the followership models below, I can identify followers I’ve been and those who have worked with me. However, literature often lacks concrete, long-term examples of how followers evolve over time and when it’s time to part ways with an organization. There is often a point where followers feel they are done collaborating with colleagues, doing what others ask, and experiencing repetitive scenarios. We don’t often discuss how to recognize this point, how to exit gracefully, and how to find new ways to be useful elsewhere. Jobs and projects don’t have to be lifelong commitments. We can be valuable in different places for different reasons, ultimately serving our organizations and leaders better. Good followership is an act of aligning ourselves with a leader and contributing to the achievement of common goals, afterall. If we are not doing this, it’s time to find a place where we can.

Definitions

- The willingness to engage in active collaboration toward shared goals, while understanding the leader’s role as the primary decision-maker.” Kellerman B. (2008)

- “The capacity and willingness to follow a leader, while exercising critical thinking, active engagement, and independent decision-making.” Riggio, R. E., Chaleff, I., & Lipman-Blumen, J. (Eds.). (2008)

- “Strong followership, as dancers know it, is at once attentive, supportive, responsible, meticulous, and expressive. This kind of following can give employees a deep sense of purpose, bring out the best in managers and supervisors, and accelerate productivity. Exceptional following enables, stabilizes, and liberates those in official leadership roles to do their jobs better, and in some ways it can even influence the scope of those jobs.” Fabiano, S. (2021)

- “The capacity to support a leader when the leader is right and to respectfully question or confront the leader when the follower believes the leader is making a mistake, being abusive, or otherwise not living up to the organization’s or the leader’s values.” Chaleff I. (2009)

- “The study of the nature and impact of followers and following in the leadership process.” Uhl-Bien, M., Riggio, R. E., Lowe, K. B., & Carsten, M. K. (2014)

- “Leadership is something we all do, not just those with a formal role, or title. Followership is something we all do, not just Frontline staff. In practical terms, everyone has a Leadership AND a followership role in an organization.” Hurwitz, M., & Hurwitz, S. (2015)

- “The process by which one accepts influences but also proactively engages with others toward common purpose.” Linville, M. W., & Rennaker, M. A. (2022)

Models

Adair’s 4-D Followership Model

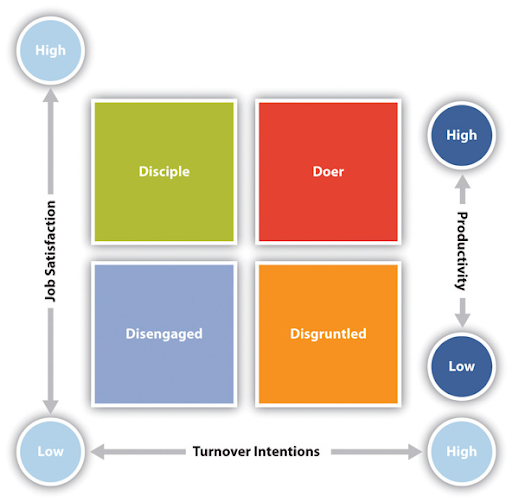

The basic model Adair proposed for understanding followers examines a follower’s level of job satisfaction and her or his productivity. Based on the combination of job satisfaction and productivity, Adair demonstrates the likelihood that someone will decide to leave the organization.

- Disgruntled

They have low levels of job satisfaction and are not overly productive at work. They have typically encountered some event within the organization that has left them feeling detached, angry, or displeased. Maybe this person was passed up for a job promotion or he or she is being bullied in the workplace. Whatever the initial trigger, these individuals are toxic to the work environment. If the disgruntled follower is caught early on in her or his downward slip into this state, there is a chance to pull her or him away from the disgruntled cliff. Unfortunately, too many leaders do not notice the signs early on and these followers either end up reacting negatively in the workplace or they job ship as soon as they get an offer. - Disengaged

This is someone who doesn’t see the value in her or his work, so he or she opts to do the minimum necessary to ensure her or his employment. Often these individuals perceive their work as meaningless or not really helping the organization achieve its basic goals, so they basically tune out. Often people who are disengaged become so because the original expectations they had for the job are simply not met, so they may feel lied to by the organization, which can lead to low levels of organizational commitment. - Doer

The third type of follower is called the doer. Doers “are motivated, excited to be part of the team. They are enterprising people, and overall are considered high producers. The only real issue with these employees is that no matter where they go in an organization, the grass always looks greener elsewhere. A doer often starts as someone who is upwardly mobile in the organization and employees become doers when one of two things occurs. First, doers want more out of life and if they don’t feel that there is continued possibilities for upward mobility within an organization, they are very likely to jump ship. Second, if a doer does not feel they are receiving adequate recognition for her or his contributions to the organization, then the doer will find someone who will give them that affirmation. - Disciple

This individual is highly satisfied and highly productive. In an ideal world, only disciples would fall under leaders because they have no problem sacrificing their own personal lives for the betterment of the organization. While some people may remain disciples for a lifetime, many more workers start as disciples and quickly become disengaged, disgruntled, or doers. This generally happens because an organization’s own employees, processes, or systems do not encourage disciple behavior and eventually wear the disciple down.

Chaleff’s Typology of Followers

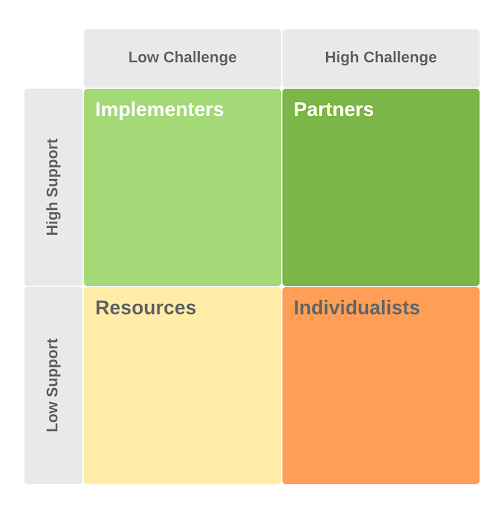

In the chart above, the dimensions have the following meaning:

- axis X – is a measure of followers’ support to their leader (low support vs. high support)

- axis Y – is how much they challenge her/him in her/his leadership (low challenge vs. high challenge)

The chart is split into 4 sub-areas:

- low support, low challenge – RESOURCES

- high support, low challenge – IMPLEMENTERS

- low support, high challenge – INDIVIDUALISTS

- high support, high challenge – PARTNERS

Each of the groups mentioned has a different impact on the organization (& the leader) and needs different leadership.

- Individualists

This individual will provide little to no support for her or his leader, but has no problem challenging the leader’s behavior and policies. This individual is generally very argumentative and/or aggressive in her or his behavior. While this individual will often speak out when no one else will, people see this person as inherently contrarian so her or his ideas are generally marginalized. - Resources

The resource is someone who will not challenge nor support the leader. This follower basically does the minimal amount to keep her or his job, but nothing more. - Partners

Partner followership occurs when a follower is both supportive and challenging. This type of follower believes that he or she has a stake in a leader’s decisions, so he or she will act accordingly. If the partner thinks a leader’s decision is unwise, he or she will have no problem clearly dissenting within the organizational environment. At the same time, these followers will ultimately provide the most (and most informed) support possible to one’s leader. - Implementers

The implementer is more than happy to support her or his leader in any way possible, but the implementer will not challenge the leader’s behavior and/or policies even when the leader is making costly mistakes. The implementer simply sees it as her or his job to follow order, not question those orders. While this kind of pure-followership may be great in the military, it can be very harmful in the corporate world.

Kelley’s Five Followership Styles

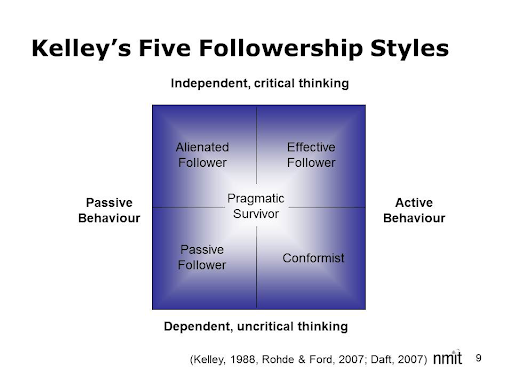

Robert E. Kelley came up with his Five Followership Styles model – between active and passive behavior AND between independent, critical thinking and dependent, uncritical thinking:

- Effective: a follower who is both a critical, independent thinker and active in behavior. They exhibit consistent behavior to all people, regardless of their power in the organization, and deal well with conflict and risk.

- Conformist: they participate very willingly but don’t question orders. They will avoid conflict at all costs and take the quietest path, but will defend their boss to loyal extremes.

- Passive: they don’t engage their brain enough, nor do they take concrete action.

- Alienated: they have got stuck where they are, are very negative, and feel they have lost their power. They have seen ‘too much’, have become bitter in their work from being passed over for promotion, or from having stayed too long in one position.

- Pragmatic Survivor: they can flip between different followership styles, to suit each situation, and are our early warning system when the organization’s culture is starting to change for the worse.

Kellerman’s Followership Model

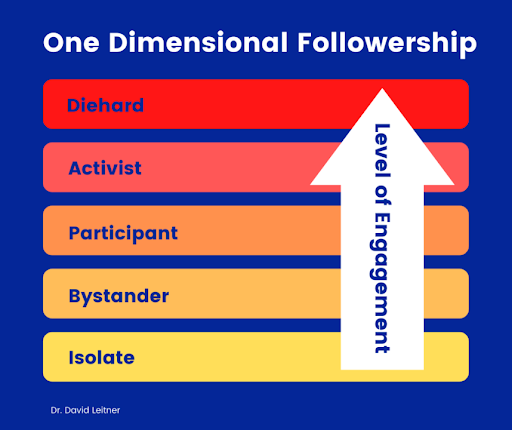

Barbara Kellerman’s Followership Model identifies 5 types of followers:

- Isolates

According to Kellerman, isolates are completely detached from and scarcely aware of what’s going on around them. They are most commonly found in larger organizations where they can fly under the radar easily as their lack of enthusiasm, innovation and hard work attracts little to no attention from leadership. - Bystanders

Unlike isolates, bystanders are aware of what’s going on around them and they do observe but they actively choose not to participate. They passively go along with leaders when it is in their self-interest to do so, but they don’t take the time or make the effort to get involved. - Participants

On the other hand, participants are engaged to an extent; they care enough to invest some time or effort into what they are doing rather than doing the bare minimum. When participants agree with leaders’ plans, aims and intentions, they can be true drivers of productivity to help the organization or department meet, but not exceed, its goals. - Activists

Activists are typically very opinionated, strong-headed, and feel strongly (either in favor of or against) their leaders; they then act according to their feelings. Followers that fall into this category are usually eager, self-motivated and highly engaged. - Diehards

Kellerman defines diehards as followers who “are prepared to go down for their cause”. By definition, they are willing to endanger their own health and welfare in the service of their cause – much like soldiers risk their lives in commitment to protecting and defending their country. Diehards are also present in less extreme situations; one example of diehard followers in an office environment is whistleblowers. Whistleblowers are dedicated to doing what they perceive to be ‘the right thing’, despite the judgment they may receive from colleagues for their unfavorable behavior.

Resources

- Adair, R. (2008). Developing great leaders, one follower at a time. In R. E. Riggio, I. Chaleff, & J. Lipman-Blumen (Eds.), The art of followership: How great followers create great leaders and organizations (pp. 137-153).

- Chaleff, I. (2009) The Courageous Follower: Standing Up to & for Our Leaders. Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Oakland.

- Fabiano, S. (2021). Lead & follow : the dance of inspired teamwork. Koehlerbooks.

- Hurwitz, M., & Hurwitz, S. (2015). Leadership is half the story: A fresh look at followership, leadership, and collaboration. University of Toronto Press.

- Kellerman B. (2008). Followership : how followers are creating change and changing leaders. Harvard Business Press.

- Kellerman, B. (2016). Leadership–It’s a System, Not a Person! Daedalus, 145(3), 83-94.

- Linville, M. W., & Rennaker, M. A. (2022). Essentials of followership: Rethinking the leadership paradigm with purpose. Kendall Hunt.

- Lundin, S. C., & Lancaster, L. C. (1990). Beyond leadership… the importance of followership. The Futurist, 24(3), 18.

- Riggio, R. E., Chaleff, I., & Lipman-Blumen, J. (Eds.). (2008). The art of followership: How great followers create great leaders and organizations. John Wiley & Sons.

- Uhl-Bien, M., Riggio, R. E., Lowe, K. B., & Carsten, M. K. (2014). Followership theory: A review and research agenda. The leadership quarterly, 25(1), 83-104.